Radical changes in the interaction between machines and humans in writing texts are underway. Artificial intelligence can automatically write, translate and edit texts. In the second part of the series, I would like to address my second thesis: Soon the question of the right publication language will be obsolete in science. I will write my scientific text in the language in which I prefer to write. The readers themselves decide in which language they want to receive it.

(This is the english translation of the original article: Wie wir in Zukunft wissenschaftliche Texte schreiben (könnten) – Teil 2)

English has undoubtedly become the most important language of publication in the academic world. This is always the subject of controversial discussions, e.g. by a political scientist, a Romance scholar and a Germanist. It is rightly argued that linguistic diversity is also important in science – although opinions differ as to whether a predominant language of publication, English, is positive on balance because it massively increases the range of publications.

I think that with the means of machine translation, the language issue for publications in science could actually already be obsolete today. However, only under certain conditions and assumptions:

- Human translations will probably still be better and for many purposes more suitable than machine translations for a very long time. Whereby it is clear that human translations also always use (and have used for a long time) machine aids.

- However, machine translations could be used selectively and adapted to the specific needs of scientific publications, so that a much greater language plurality could be lived in science.

- Crucially, we do not primarily need „covert“ translations in science, but „overt“ translations (House 2005). Intelligent, AI-assisted machine translation opens up entirely new possibilities here.

Juliane House compares different translation concepts that have a long tradition and distinguishes „overt“ from „covert“ processes. Put simply, covert translations aim to produce a text in the target language in which its origin and source language are, in the best case, no longer visible at all. It should not only be linguistically perfectly adapted to the target language, but also incorporate the contexts and cultural characteristics of the target language and target culture.

Open translation is different: it aims to make as transparent as possible what the cultural context of the source text is. As a result, the translation may be more difficult to understand, but it gives a clear picture of the conditions under which the text was created.

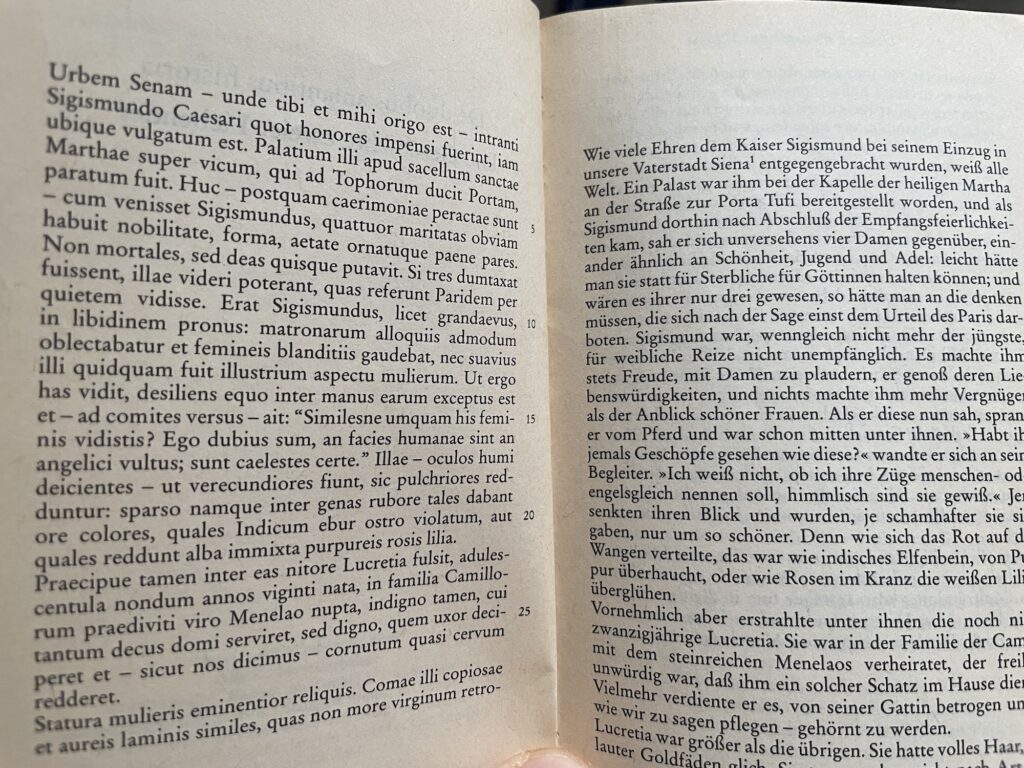

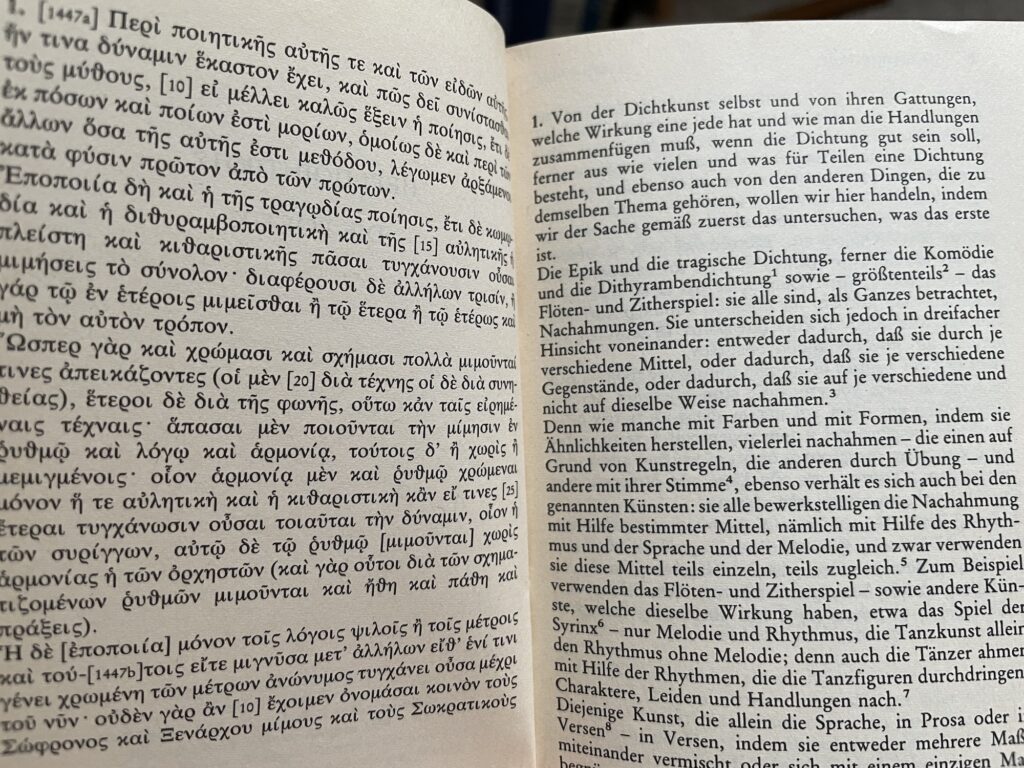

We are very familiar with this tradition of open translations, for example in the form of parallel texts, bilingual annotated editions (or glosses as translation aids in medieval Latin manuscripts). Here are examples of Piccolomini’s Euryalus and Lucretia in Latin and German, and of Aristotle’s Poetics Greek/German:

This is what we need for scientific publications – but combined with the new possibilities of AI and machine translation.

Using ChatGPT as an example of powerful AI, for example, the following is possible:

Prompt: Please translate the following text in English, but add the original after each sentence and format according to the following pattern: English sentence. German original.. Here is the text to be translated:

[German Text]Answer: <span lang=“en“>When it comes to writing scientific texts […] </span> <span lang=“de“>Wenn es um das Schreiben von wissenschaftlichen Texten geht […] </span>

ChatGPT dialogue of 15. 12. 2022 (translated, original in German)

This is not very exciting; cleverly formatted, however, it can be used to generate a text view where the original is displayed when the mouse hovers over the sentence if required.

But it gets more interesting with the following step:

Prompt: Very good. Now mark additional words in the English text where the translation is uncertain. Mark them according to the following pattern: english expression (engl: German original). Add a span element with title attribute, in which you give an explanation why the translation is uncertain.

Output (in HTML – here view in browser):

ChatGPT dialogue of 15. 12. 2022 (translated, original in German)

This results in a new way of dealing with machine translation in science, as this process can be automated to a large extent. A journal could allow authors to submit their texts in (almost) any language. When the text is published, the reader can decide on the output language himself – or more precisely: receives an open translation in the parallel text. This form of translation allows:

- The original is visible or invisible to any degree: if, for example, I as a reader understand the original language passively quite well and have only minor uncertainties, the original may be very present. If the original language is largely incomprehensible to me, then the open translation must be primarily visible.

- Passages, expressions where the machine translation is uncertain (or errors typically happen, cf. Czulo et al. 2022) are marked accordingly: Here I am warned, informed about the possible uncertainties, and advised to look into the original.

Already the author of the text marks important passages in the text, e.g. terminology, definitions or the like, to which special attention must be paid during translation. Based on the structure of the text, an AI can also make suggestions during writing as to what such critical passages might be.

The other capabilities of the AI also allow for additional assistance. For example, summaries can easily be created in a language other than the original.

Of course: none of this replaces human-generated translations, whether overt or covert. However, given the large number of academic publications, this is an obvious way to increase the quality of academic work, because:

- Participation is increased as language barriers fall.

- Linguistic engagement with one’s own text (as the author expects possible machine translations) increases sensitivity to different cultural contexts and differences in meaning.

Probably linguistic diversity is not equally important for all scientific disciplines. But it certainly is for large parts of the humanities and social sciences

Already published:

- Part 1: Writing and research support by AI: Artificial intelligence systems for generating texts will not produce meaningful scientific texts, but will be a huge help to us in writing and research.

Bibliography

Stöcklin, Stefan. Wissenschaftssprache: “Sprachliche Diversität ist fruchtbar”. Interview mit Angelia Linke, Peter Fröhlicher und Fabrizio Gilardi. UZH News. https://www.news.uzh.ch/de/articles/2017/englisch-debatte.html. (2017).

House, Juliane. 2005. Offene und verdeckte Übersetzung: Zwei Arten, in einer anderen Sprache ›das Gleiche‹ zu sagen. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 35(3). 76–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03379444.

Czulo, Oliver, Venema Victor, Jo Havemann, Jennifer Miller & Dasapta Irawan. Caveats of machine translation – Translate Science Blog. https://blog.translatescience.org/caveats-of-machine-translation/. (18 December, 2022).

Bubenhofer, Noah. 2020. Visuelle Linguistik: Zur Genese, Funktion und Kategorisierung von Diagrammen in der Sprachwissenschaft. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110698732.

Pingback: How we (could) write scientific texts in the future – part 1 | Sprechtakel